Three long, agonizing days have passed since the unspeakable events in Peshawar on December 16. As people everywhere grapple with a tragedy that is beyond comprehension, the one thing that unites all Pakistanis – indeed, all those who care for humanity – is the desire to do whatever it takes to fight back against the forces that unleashed this horror. Knowledgeable Pakistanis and others have written insightful analyses, offered moving pleas, expressed new hope, and made important suggestions. There has been a gratifying upsurge of revulsion against extremists that is already producing some concrete results. But this is now, while the tragedy is still fresh in our hearts. What of the longer term?

As human beings, we all know that the solidarity that we see now will fade over time; the old differences will resurface; the grief will dissipate, except for the families that actually suffered the loss of loved ones. In this age of distraction, unity of purpose is ephemeral, and unity of action even more so. Thus, it is critical that this passing period of common rage and determination be used to set up concrete plans and policies that will outlive our rage and achieve our purposes.

The immediate response to the tragedy will come from the military, the intelligence services, the police, and the political leadership of the country. The military response will be swift and brutal, as it should be. And even the politicians may be able to overcome their petty differences sufficiently to put better policies in place. But the problems epitomized by the Peshawar attack were not created in a few months or years, and will not be solved quickly. The question is whether the state of Pakistan will make long-term changes that begin moving us towards a solution.

The cynic in me is skeptical, and this skepticism is sharedby otherswho have followed the history of Pakistan. However, it is also true that great calamities sometimes produce permanent changes that had appeared impossible before. Perhaps this massacre of innocents will be such a “hinge event” for Pakistan, but to make it so will require answering some hard questions and making some difficult decisions. So, first the questions:

Question 1: Who is to be considered a “terrorist”?

Will this term be applied narrowly to those who directly challenge state institutions such as the Army, or broadly to all those who attack innocent people in the name of anyideology or political purpose. This is not an issue peculiar to Pakistan – the post-9/11 West has faced and failed to solve this problem. But clarity on this issue is especially important in the context of Pakistan. This is because, unlike the situation in, say, Sri Lanka with the Tamil Tigers, terrorism in Pakistan is not rooted in a single concrete causebut in a state of mind. This state of mind can, and does, promote diverse causes: Enforcing strict religious laws; combating India; suppressing sectarian rivals; creating a new caliphate; and even hastening the Day of Judgment. With such a breadth of incommensurate and sometimes irrational purposes, one must define terrorism not by its goals or its targets, but by its underlying ideology. The thing that unites all those who kill innocents en masse in Pakistan (and indeed, all over the world) is their deviant view of the value of human lives – they love their cause more than they love their fellow humans. The term “human” is critical here – not “Muslim” lives, or “military” lives, or “Pakistani” lives, but “human” lives. Unless we use this greatest common denominator as our definition, we will continue to distinguish between “good” terrorists and “bad” terrorists– and perhaps also some “neutral” terrorists who kill people we just don’t care much about. Even the term “Taliban” is insufficient, since many terrorist groups don’t use that name. But once we recognize the primacy of protecting all human lives, it is easy to determine who is a terrorist, regardless of whether they fight for religious, sectarian, nationalist or metaphysical causes. It is abundantly clear that groups (such as the Tehrik-e-Taliban Pakistan (TTP)) that target military personnel are closely linked with groups that target their sectarian rivals and specific communities such as Shi’as, Ahmadis and Christians. Unless both types of groups are included in the definition of “terrorists”, pools of infection will survive in Pakistan and will continue to infect the population in the future.

Question 2: Where do the terrorists get their ideology?

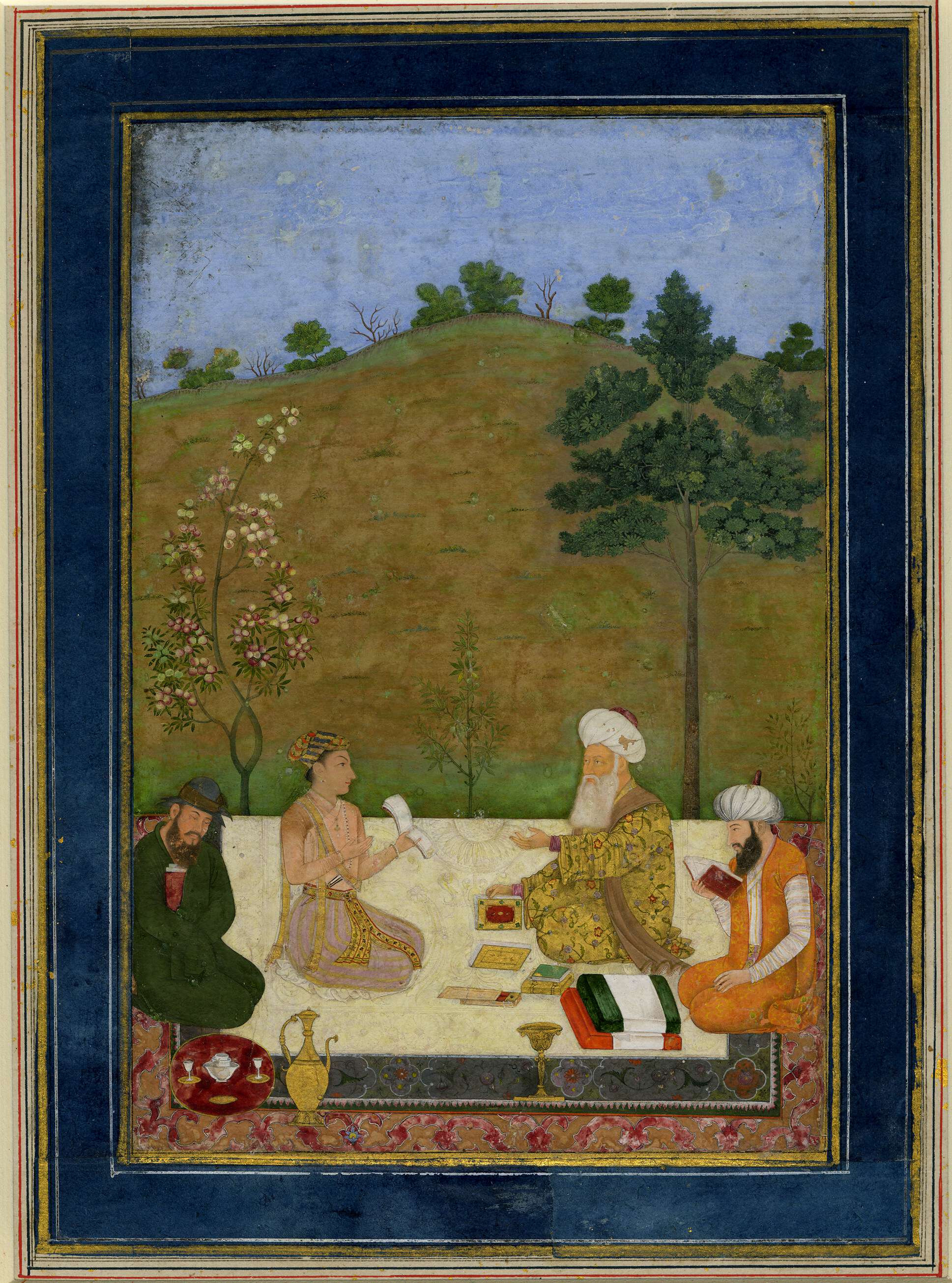

The painful answer here is that, in the case of Pakistan, they get their ideology from an exceptionally literalist, inhumane and narrow-minded interpretation of Islam. Like all great religions with a substantial history, Islam has had many forms and interpretations in different times and places. This plurality has largely been accepted by Muslim societies, with some notably bloody exceptions. The form of Islam that has dominated in the areas of Pakistan for many centuries is a relatively open-minded, even syncretic, version of the sufi tradition. However, much more austere and puritanical interpretations have sporadically infiltrated the region from both the east and the northwest. This infiltration became more sustained during the colonial and post-colonial periods – through the emergence of pan-Islamist ideas, the ideologically rooted movement for the creation of Pakistan, the rise of political Islam in the form of Jamaat-e-Islami, the influence of ultra-orthodox seminaries, the influx of more orthodox Muslims, and, most importantly, the importation of the Wahhabi ideology from Saudi Arabia during the years of Gen. Zia-ul-Haq and the Afghan jihad against the Soviets. Today, violence in the name of Islam is perpetrated by groups aligned with different Muslim sects, with targets varying accordingly, but all these groups ultimately derive their zeal from the same attitude: Regarding those with differing beliefs as inferior and worthy of elimination (waajib-ul qatl).

Question 3: Why does religious extremism lead to terrorism?

Traditionally, extreme religiosity has manifested itself in asceticism and piety, not violence. What is it about Muslim extremism in the 21stcentury that leads inevitably to violence? The answer lies in the way Muslims – not just extremists – have come to relate to their faith in recent times. Following its early expansion, Islam quickly shed any puritanical tendencies it had, becoming an instrument of politics at the collective level and a vehicle for piety at the personal level. Kings – even if they were called Caliphs – could not countenance a supra-royal orthodoxy and, contrary to popular belief, the history of Muslim societies is one of religious flux rather than rigid orthodoxy – punctuated occasionally by orthodox-minded kings such as Aurangzeb Alamgir. Extremists of the kind we see today have always existed, but they have been treated as rebellious outsiders (khawaarij) and suppressed strongly by the state. The celebration of such groups as heroic is a phenomenon rooted in more recent history – particularly in the revivalist vision with which many Muslim societies responded to colonial subjugation. This vision saw deviation from the “true” faith as the main cause of Muslim decline, and sought to purify Islam by returning it to its founding principles. This attitude of originalism (which is much broader than just the Salafism of Wahhabis) is a major source of violent fervor among Muslims today, enabled particularly by three core aspects: 1) Belief in a mythologized history; 2) A strongly bipolar view of the world in terms of believers and unbelievers; and 3) A literalist view of Islam and its practice. All three strains have acquired special power in modern Pakistan through the revivalist ideological narrative underlying the creation of the country. The vision of Pakistan was sold to many – both before Partition and after – as that of an ideal “fortress of Islam” that would revive the polity of the original “State of Madina” under the Prophet Muhammad. Politicians still use this trope to move their supporters. Of course, if Pakistan is to be the fortress of Islam, it must have ferocious enemies, which are conveniently available in the form of Christians, Jews, Hindus, etc. And finally, if Pakistan is truly to revive the State of Madina, its people must follow the original laws and texts of that state, not just in spirit but in letter. From there, it is a short step to believing in the virtue of fighting unbelievers, oppressing minorities and accepting laws such as the blasphemy law, which prescribes irrevocable capital punishment for any disrespect of Islam. Unfortunately, these attitudes are not confined to a few fringe extremists, but are widely accepted by the Pakistani populace. They have been woven into the distorted curricula taught in schools, reinforced by the rhetoric of a religiously-defined nationalism, and promoted by the media through the amplification of bigoted voices. The government of Pakistan has systematically created an institutional framework to support this ideology through laws and courts. The extremists have not needed to create intolerant attitudes; government and society have already done that. The extremists just take the ideas to the extreme – some might say, to their logical conclusion – identifying suicide bombing with martyrdom, narrowing the circle of believers to only their sect, and enforcing the blasphemy laws through vigilante action. These extreme positions are possible only because less extreme versions of them are considered mainstream, making it almost impossible to denounce the extremism without risking a charge of blasphemy. This has to change if Pakistani society is to make any real progress against terrorism.

Question 4: Why does the state allow these attitudes to persist in Pakistani Society?

The single biggest factor that allows the attitudes described above to persist is the fractured state of the Pakistani state: Every political party and religious group has its own exclusive center of power; the military is a state unto itself, with its own policies and purposes; and the intelligence services are widely believed to comprise an even “deeper” state that links up with extremist groups. Even the traditionally weak Pakistani judiciary has shown signs of “going rogue” in recent years, not always to the benefit of society at large. All these centers of power sponsor specific narratives to exploit patriotism, ideology and religion for their own purposes. In the prehistoric days of exclusive state control over the media, this made little impact on the public, but in today’s laudably open and cacophonous media environment, every narrative can find a voice, leaving people confused and seeking certainty. Too often, this certainty is provided – by the same agents through the same media – in the form of bizarre conspiracy theories that rapidly become part of the national psyche, going from rumor to fact to belief, and often connecting up with pre-existing ideological and religious dogma. Dwelling in this forest of whispers, it is hardly surprising that many people lose touch with the reality of the rest of the world and slip into a state of mind where a mythology of millennial wars, dark forces and the Hand of God guiding history begins to make sense. The romance of crusaders, fortresses, black banners and caliphates emerges from this, and is nurtured by the fictional history taught to the populace.

Again, this is not a peculiarly Pakistani or Muslim phenomenon – most countries have their national mythologies, in some cases connecting with actual ancient mythologies (as with India and Israel) or seeing the Hand of God or Destiny in their affairs (as with the British Empire and the United States). The difference with Pakistan (and to some degree in Israel) is that the myths have become central to national identity and even policy-making.

So how can all this be changed?

It is tempting to embrace an ultra-authoritarian model like that of Ataturk in Turkey and now Sisi in Egypt, secularizing the country by force and squashing dissent. History suggests that this is unlikely to work and can be exceptionally dangerous. First, it is impossible to guarantee that dictators in an authoritarian state will always be enlightened – in fact, that is very unlikely (see Mugabe, Robert G.) Second, deep beliefs do not disappear in a few generations because they have been suppressed by force. The case of Muslim Central Asia is instructive: A population indoctrinated into strict communist ideology for decades has now become a fertile source of jihadists for extremist groups everywhere. And Turkey, which was the most successful example of top-down secularization in the Muslim world, is rapidly moving back to the old ways before our eyes. The Chinese experiment goes on, but there are too many differences for it to apply directly to Pakistan.

It is also important to realize that, in today’s complex world, the state can only make a limited impact in trying to change society. Any change towards a moderate, enlightened Pakistan must come from the people. I believe that this is very possible, because most of the people who live in the country come from an open-minded tradition, and still celebrate it in many aspects of their culture. The role of the state should be to reconnect people to that tradition, and to remove, as far as possible, the factors that impede this reconnection. It is also futile to propose radical ideas such as declaring Pakistan a secular state or immediately normalizing all relations with India. Sensible as these ideas may be, they will take root only if they develop organically within the society rather than being imposed in Kemalist fashion. The key is that the trajectory of Pakistan must be changed – both by its people and by the state. What the people must do is a complex topic that I will leave for another time, but here is

a (necessarily incomplete) to-do list:

Implement fundamental reforms in the educational system

Educational curricula at all levels should be changed to emphasize a modern, rational, inclusive world-view rather than the obscurantist, hyper-nationalist, mythologized and exclusivist narrative that exists today. This will require: a) Teaching real history rather than a fictional one; b) Focusing broadly on world history rather than just on the history of Pakistan; c) Exposing students to the history of ideas, not just the history of events and personalities; d) Encouraging the habits of critical thinking and skeptical inquiry rather than a mindset of received certainties; and e) Emphasizing engagement with the world of human endeavor through the sciences, arts and humanities rather than immersing students in abstractions of religious dogma. Let young minds learn that what we make of this world depends on natural forces and human actions, and that morality comes from social responsibility rather than religious edicts.

Highlight the diversity of interpretations within Islam rather than supporting a single orthodoxy

Contrary to popular myth, puritanical beliefs are not the only standard ones held by Muslims through the centuries. They often come from more recent interpretations by the clerical class to whom the public has ceded all religious interpretation. If there’s one thing that the state must do to combat extremism, it would be to change this religious narrative. At the present time, the amount of pure hate preached from pulpits and taught in seminaries all over the Muslim world is mind-boggling. Ordinary people who live immersed in this miasma are easily conditioned to accept such beliefs as part of their faith. The state must provide alternatives to this – not by creating some new “official version” of Islam, but simply by highlighting the many interpretations of Islam that have been held in Muslim societies throughout history. Extremism does not come naturally to human beings, and exposure to the truth will always bring moderation.

Combat the cult of death by respect for life

The terrorists thrive on the idea of embracing death in the hope of rewards in the hereafter. This allows them to devalue the lives of everyone who disagrees with them. The best way to combat this is to oppose it with a system that values all human lives- not just Muslim lives. There is vast justification for this within the Islamic tradition, but it needs to be codified into the law of the land. The political rhetoric must also change accordingly from exclusivist to inclusive –emphasizing equal respect for all communities within society. Most importantly, the state must not allow the use of hate speech to stoke violence against any group. A bright line must be drawn between personal free speech, which should be protected, and incitement, which must be curtailed. People should be free to express hateful views as individuals, but not from pulpits or in public forums. And under no circumstances must the institutions of the state be perceived as supporting or condoning such speech. Let the purveyors of hate live, but as social and official pariahs.

Unify the structures of government around service to society

No state can survive if it is at war with itself. The current situation where power groups within the government act to advance their own narrow agendas has to change, and all these groups have to align themselves towards a single purpose. In a modern state, this purpose can only be service to society at large. Each institution will play a different part in this, but all must agree on the same principles. Ideally, these must come from the elected civilian leadership, but if they must be negotiated with greater participation from the military and other institutions, so be it. The core element that must not be sacrificed is a system of mutual checks and balance between the institutions of power.

Stop using militants as “strategic assets”

There is a long and instructive history of societies using mercenary militant groups as weapons against their opponents. In almost all such cases, the militants turned against their patrons at catastrophic cost to the latter. The classic example of this in Muslim history is the invitation of the fundamentalist Berber group Al-Muraabitoon (Almoravids) by Muslim rulers in Spain to fight against their Christian foes. The group did fight Christians effectively, but also found their own Muslim sponsors insufficiently Islamic and proceeded to destroy them. A similar process has unfolded in Pakistan, where extremist groups have been nurtured as “strategic assets” by hyper-nationalist forces within the power structure, mainly for use against arch-foe India, to (unsuccessfully) create a zone of influence in Afghanistan and possibly to combat the influence of Shi’a Iran. Like wild beasts kept as pets, these groups are now devouring their keepers. It should be easy to decide that this strategy has failed, and to stop feeding the beasts, but this will require giving up dreams of an Indian reconquista and a new caliphate. Recent reports (pre-Peshawar) suggest that this has not yet happened.

Stop promoting conspiracy theories and blaming others

It is tempting for any individual or group to ascribe their problems to circumstances beyond their control, but enough already with conspiracy theories! Even today, after the TTP have loudly accepted responsibility for Peshawar, “responsible” people are out in the media blaming the massacre on India.

Pakistan does have real enemies, but most of what ails it has come from its own misguided policies. The Crusader-Zionist-Brahmin axis, the CIA-Mossad-RAW alliance, the Protocols of the Elders of Zion, the ubiquitous “foreign hand”, the impending arrival of “Dajjal” (the Antichrist), secret atmospheric weapons (HAARP) causing floods and earthquakes, 9/11 trutherism – these and many other outlandish conspiracy theories rife in Pakistan serve only to distract people from the real authors of their woes. Ultimately, these can only be combated by a better educational system, but to the extent that these theories are promoted by specific power groups for their own narrow agendas, they can be controlled at the source. The institutions themselves should develop cultures where propagating such conspiracy theories is cause for ridicule. In particular, the nexus between religious fantasies and conspiracy theories must be broken.

Engage with the world

The wonderful world we live in is the best teacher and moderator of humans. A big factor behind the profusion of outlandish ideas in Pakistani society is disengagement from the world. While the Internet and social media have brought people closer across traditional barriers, this is a distorted connection at best. More Pakistanis – especially young people – need to experience the diversity of the world first-hand. The best way to do that is for the government to support international travel and exchange programs for youth, which would allow students of high school and college age to spend significant time in other countries – notably those which are seen with the greatest suspicion, i.e., India and Western countries. Such exposure at an impressionable age will give Pakistani youth a real sense of the world and its pluralism, making it more difficult for obscuranist forces to infect their minds with thoughts of jihad and martyrdom.

As I write this, the outrage is still pouring in, but it is too early to know if any of the changes suggested above will actually occur, or if the questions raised here will be answered honestly. The establishment has built the current structure with great effort, and there will be many who are still reluctant to let go. To these, the people of Pakistan must speak loud and clear: The time for vacillation is over. The cause is clear and the enemy obvious. Those who still obfuscate these issues must be consigned to the garbage-can of history.

The urgency of the hour notwithstanding, real change will take time – decades and generations, not months and years, and most of it will come from the people, not the state. Much will change during this time in ways that we cannot imagine today, and not always for the better. The war that is underway now is unlikely to be short, and though its details may still remain in flux, it is critical to acknowledge the nature of this war. It is not a war between believers and unbelievers, Shi’as and Sunnis, or the West and the Muslim world. It is a war between two visions of life and death; not a clash of civilizations, but a war for civilization. On one side are nihilists who value their beliefs more than the lives of their fellow humans, see this world as ephemeral, and seek their rewards in the hereafter. On the other are those who do care for other human beings and, however imperfectly, want to understand and improve this world. No society interested in thriving can possibly choose the nihilist side over the long term, even if it is dressed up in the garb of faith. Therefore, I will go out on a limb and predict that the day will come when Pakistan, India, Afghanistan, Iran, Syria, Saudi Arabia, Turkey, Israel, China, Russia, the United States and many others will all fight as allies against an amorphous jihadist threat stretching from Morocco to Indonesia. It may take ten years, or twenty, to get there, but that’s where things are going whether we like it or not, and we will all need to decide which side we stand on.